Let’s

wrap up our month of Medieval music by looking at a very important genre that

developed in the early 13th century – the motet. This type of polyphony adds a newly-written

Latin text to the upper voices of clausulae. Wait – what does that mean?

“Clausulae” were sections of organum (see my last post!) that could be removed

and replaced with a new section. Therefore, a motet contained a new text sung

with a lower part that usually was taken from chant. Eventually more voices

were added, singing their own individual texts. The motet developed in form

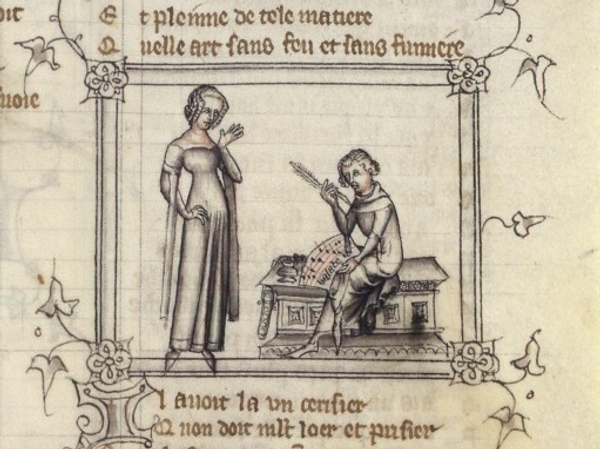

over time and was performed both inside and outside of the church. One example

of a leading motet composer is Guillaume de Machaut.

|

| Guillaume de Machaut Courtesy of wikimedia.org |

Around

this time, we see more developments in notation including note duration

signified by note shapes – quite similar to how we notate music today! Also, we

see mensuration signs, the ancestor to modern-day time signatures.

Next

month, we’re taking a leap forward in time and hitting our annual music and

cinema month in Clef Notes! Join me as we look at our favorite films and how

music plays a major part.